A higher resolution scan of the image. - 2248595 bytes

First, some technical comments on this page:

- The image you see here is slightly "bleached". I used Photoshop to remove some of the foxing present in the original.

- The text "pages" (below) are formatted in as close approximation to the original as possible with the idea to include the text not as an image but in a searchable format.

- That said, I was unable to properly justify the text and include the proper line breaks. I kept the line breaks, and allowed the text to justify left.

- I have included the printer's mistakes such as the missing 'S' in the title on page 130 and the "lone" 9 on the bottom of page 129.

- The color of the "pages" below are set to a close approximation of the tone of the paper of my copy.

Some comments more to the point of the page:

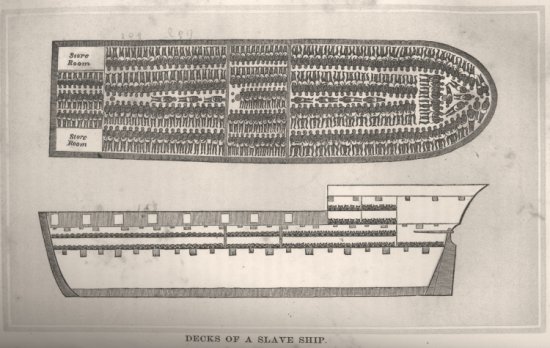

I recently acquired this image (and book) and thought that it would be an interesting addition to the site. The image of the placement of slaves on a ship is a popular reference used when trying to visually convey the conditions of the middle passage. (What pictorial US history book does not include a similar picture?) When I found this image I wished to share it primarily for its popularity in that respect.

After reading some of the book I decided it was insufficient to just include the image, and not some of the text. The image conveys a uniform neatness in the Middle Passage that the text does not. I include the text of chapter ten here to give a better, more complete, view of the situation.

THE HISTORY

OF

SLAVERY AND THE SLAVE TRADE,

ANCIENT AND MODERN.

THE FORMS OF SLAVERY THAT PREVAILED IN ANCIENT NATIONS,

PARTICULARLY IN GREECE AND ROME.

THE AFRICAN SLAVE TRADE

AND THE

POLITICAL HISTORY OF SLAVERY

IN THE

UNITED STATES.

COMPILED FROM AUTHENTIC MATERIALS

BY W. O. BLAKE

COLUMBUS, OHIO:

PUBLISHED AND SOLD EXCLUSIVELY BY SUBSCRIPTION

BY J. & H. MILLER.

1857.

CHAPTER X.

AFRICAN SLAVE TRADE IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, CONTINUED.--THE

MIDDLE PASSAGE.

Abstract of Evidence before House of Commons, continued.--The enslaved Africans on

board the Ships--their dejection.--Methods of confining, airing, feeding and exerci-

sing then.--Mode of stowing them, and its horrible consequences.--Incidents of the

terrible Middle Passage--shackles, chains, whips, filth, foul air, disease, suffocation.--

Suicides by drowning, by starvation, by wounds, by strangling.--Insanity and Death.

--Manner of selling them when arrived at their destination.--Deplorable situation

of the refuse or sickly Slaves.--Mortality among Seamen engaged in the Slave Trade.

Their miserable condition and sufferings from disease, and cruel treatment.

THE natives of Africa having been made slaves in the modes described in

the former chapter, are brought down for sale to the European ships. On

being brought on board, says Dr. Trotter, they show signs of extreme distress

and despair, from a feeling of their situation, and regret at being torn from

their friends and connections; many retain those impressions for a long time;

in proof of which, the slaves on board his ship being often heard in the night

making a howling melancholy noise, expressive of extreme anguish, he repeat-

edly ordered the woman who had been his interpreter to inquire into the

cause. She discovered it to be owing to their having dreamed they were in

their own country again, and finding themselves, when awake, in the hold of a

slave-ship. This exquisite sensibility was particularly observable among the

women, many of whom, on such occasions, he found in hysteric fits.

The foregoing description, as far as relates to their dejection when brought

on board, and the cause of it, is confirmed by Hall, Wilson, Claxton, Ellison,

Towne, and Falconbridge, the latter of whom relates an instance of a young

woman who cried and pined away after being brought on board, who recovered

when put on shore, and who hung herself when informed she was to be sent

again to the ship.

Captain hall says, after the first eight or ten of them come on board, the

men are put into irons. They are linked two and two together by the hands

and feet, in which situation they continue till they arrive in the West Indies,

except such as may be sick, whose irons are taken off. The women, how-

ever, he says, are not ironed. On being brought up in a morning, says Surgeon

Wilson, and additional mode of securing them takes place, for to the shackles

of each pair of them there is a ring, through which is reeved a large chain,

which locks them all in a body to ring-bolts fastened to the deck. The time

of their coming up in the morning, if fair, is described by Mr. Towne to be

between eight and nine, and the time of their remaining there to be till four in

the afternoon, when they are again put below till the next morning. In the

interval of being upon deck they are fed twice. They have also a pint of

water allowed to each of them a day, which being divided is served out to

them at two different times, namely, after their meals. These meals, says Mr.

Falconbridge, consist of rice, yams, and horse-beans, with now and then a

little beef and bread. After meals they are made to jump in their irons.

This is called dancing by the slave-dealers. In every ship he has been desired

to flog such as would not jump. He had generally a cat-of-nine-tails in his

hand among the women, and the chief mate, he believes, another among the men.

The parts, says Mr. Claxton, (to continue the account,) on which their

shackles are fastened, are often excoriated by the violent exercise they are thus

forced to take, of which they made many grievous complaints to him. In his

ship even those who had the flux, scurvy, and such œdemtatous swellings in

their legs as made it painful to them to move at all, where compelled to dance

by the cat. He says, also, that on board his ship they sometimes sung,

but not for their amusement. The captain ordered them to sing, and they

sung songs of sorrow. The subject of these songs were their wretched situa-

tion, and the idea of never returning home. He recollects their very words

upon these occasions.

The above account of shackling, messing, dancing, * and singing the slaves,

is allowed by all the witnesses, as far as they speak to the same points, except

by Mr. Falconbridge, in whose ships the slaves had a pint and a half of water

per day.

On the subject of the stowage and its consequences, Dr. Trotter says that

the slaves in the passage are so crowded below, the it is impossible to walk

through them, without treading on them. Those who are out of irons are

locked spoonways (in the technical phrase) to one another. It is the first

mate's duty to see them stowed in this way every morning; those who do not

get quickly into their places, are compelled by a cat-of-nine-tails.

When the scuttles are obliged to be shut, the gratings are not sufficient for

airing the rooms. He never himself could breath freely, unless immediately

under the hatchway. He has seen the slaves drawing their breath with all

those laborious and anxious efforts for life, which are observed in expiring

animals, subjected by experiment to foul air, or in the exhausted receive

of an air pump. He has also seen them, when the tarpaulings have inadvert-

ently been thrown over the gratings, attempting to heave them up, crying out

in their own language, "We are dying!" On removing the tarpaulings and

gratings, they would fly to the hatchway with all the signs of terror and dread

of suffocation. Many of them he has seen in a dying state, but some have re-

covered by being brought hither, on on the deck; others were irrecoverably

lost by suffocation, having had no previous signs of indisposition.

Mr. Falconbridge also states on this head, that when employed in stowing

the slaves, he made the most of the room and wedged them in. They had not

so much room as a man in his coffin, either in length or breath. It was im-

possible for them to turn or shift with any degree of ease. He has often

occasion to go from one side of their rooms to the other, in which case he

always took off his shoes, but could not avoid pinching them; he has the

marks on his feet where they bit and scratched him. In every voyage, when

the ship was full, they complained of hear and want of air. Confinement in

this situation was so injurious, the he has known them to go down apparently in

good health at night, and found dead in the morning. On his last voyage he

opened a stout man who so died. He found the contents of the thorax and

abdomen healthy, and therefore concludes he died of suffocation in the night.

He was never among them for ten minutes below together, but his shirt was as

wet as if dipped in water.

One of his ships, the Alexander, coming out of Bonny, got aground on the

bar, and was detained there six or seven days, with a great swell and heavy

rain. At this time the air ports were obliged to be shut, and part of the

gratings on the weather side covered: almost all the men slaves were taken ill

with the flux. The last time he went down to see them, it was so hot he took

off his shirt. More than twenty of them had fainted, or were fainting.

* The necessity of exercise for health is the reason given for compelling the slaves to

dance in the above manner.

He got however, several of them hauled on deck. Two or three of these

died, and most of the rest, before they reached the West Indies. He was

down only about fifteen minutes, and became so ill by it that he could not get

up without help, and was disabled (the dysentery seizing him also) from doing

duty the rest of the passage. On board the same ship he has known two or

three instances of a dead and living slave found in the morning shackled

together.

The crowded state of the slaves, and the pulling off the shoes by the sur-

geons, as described above, that they might not hurt them in traversing their

rooms, are additionally mentioned by surgeons Wilson and Claxton. the

slaves are said also by Hall and Wilson to complain on account of heat.

Both Hall, Towne, and Morley, describe them as often in a violent perspira-

tion. or dew sweat. Mr. Ellison has seen them faint through heat, and obliged

to be brought on deck, the steam coming up through the gratings like a fur-

nace. In Wilson's and Towne's ships, some have gone below well in even-

ing, and in the morning have been found dead; and Mr. Newton has often

seen a dead and living man chained together, and to use his own words, one

of the pair dead.

To come now to the different incidents on the passage. Mr Falconbridge

says that there is a place in every ship for the sick slaves, but there are

no accommodations for them, for they lie on the bare planks. He has seen

frequently the prominent parts of their bones about the shoulder-blade and

knees bare. He says he cannot conceive any situation so dreadful and dis-

gusting as that of slaves when ill of the flux; in the Alexander, the deck was

covered with blood and mucus, and resembled a slaughter-house. The stench

and foul air were intolerable.

He has known several slaves on board refuse sustenance, with a design

to starve themselves. Compulsion was used in every ship he was in to make

them take their food. He has known also many instances of their refusing to

take medicines when sick, because they wished to die. A woman on board the

Alexander was dejected from the moment she came on board, and refused

both food and medicine: being asked by the interpreter what she wanted, she

replied, nothing but to die--and she did die. Many other slaves expresses

the same wish.

The ships, he says, are fitted up with a view to prevent slaves jumping over-

board; notwithstanding which he has known instances of their doing so. In

the Alexander tow were lost in this way. In the same voyage, near twenty

jumped overboard out of the Enterprise, Capt. Wilson, and several from a

large Frenchman in Bonny River. In his first voyage he say at Bonny, on

board the Emilia, a woman chained to the deck, who, the chief mate said, was

mad. On his second voyage, there was a woman on board his own ship, whom

they were forced to chain at certain times. In a lucid interval she was sold at

Jamaica. He ascribes this insanity to their being torn from their connections

and country.

Doctor Trotter, examined on the same subject, says that the man sold with

9

his family for witchcraft, (of which he has been accused, out of revenge, by a

Cabosheer,) refused all sustenance after he came on board. Early next morn-

ing it was found he had attempted to cut his throat. Dr. Trotter sewed up

the wound, but the following night the man had not only torn out the sutures,

but had made a similar attempt on the other side. From the ragged edges of

the wound, and the blood upon his finger ends, it appeared to have been done

with his nails, for though strict search was made through all the rooms, no in-

strument was found. He declared he never would go with white men, uttered

incoherent sentences, and looked wishfully at the skies. His hands were se-

cured, but persisting to refuse all sustenance, he died of hunger in eight or ten

days. He remembers also an instance of a woman who perished from refusing

food: she was repeatedly flogged, and victuals forced into her mouth, but no

means could make her swallow it, and she lived for the four last days in a state

of torpid insensibility. A man jumped overboard, at Anamaboe, and was

drowned. Another also, on the Middle Passage, but he was taken up. A

woman also, after having been taken up, was chained for some time to the mizen-

mast, but being let loose again made a second attempt, was again taken up, and

expired under the floggings given her in consequence.

Mr. Wilson, speaking also on the same subject, relates, among many cases

where force was necessary to oblige the slaves to take food, that of a young

man. He had not been long on board before he perceived him get thin. On

inquiry, he found the man had not taken his food, and refused taking any.

Mild means were then used to divert him from his resolution, as well as prom-

ises that he should have any thing he wished for: but still he refused to eat.

They then whipped him with the cat, but this also was ineffectual. He always

kept his teeth so fast, that it was impossible to get any thing down. They

then endeavored to introduce a speculum oris between them; but the points

were too obtuse to enter, and next tried a bolus knife, but with the same effect.

In this state he was for four or five days, when he was brought up again

in the same state as before. He then seemed to wish to get up. The crew

assisted him, and brought him aft to the fire-place, when, in a feeble voice, in

his own tongue, he asked for water, which was given him. Upon this they

began to have hopes of dissuading him from his design, but he again shut his

teeth as fast as ever, and resolved to die, and on the ninth day from the first

refusal he died.

Mr Wilson says it hurt his feelings much to be obliged to use the cat so

frequently to force them to take their food. In the very act of chastise-

ment, they have looked up at him with a smile, an in their own language

have said, "presently we shall be no more."

In the same ship a woman found means to convey below the night preceding

some rope-yarn, which she tied to the head of the armorer's vice, then in the

women's room. She fastened it round her neck, and in the morning was found

dead, with her head lying on her shoulder, whence it appeared, she must have

used great exertions to accomplish her end. A young woman also hanged her-

self, by tying rope-yarns to a batten, near her usual sleeping-place, and then

slipping off the platform. The next morning she was found warm, and he

use the proper means for her recovery, but in vain.

In the same ship also, when off Annabona, a slave on the sick list jumped

overboard, and was picked up by the natives, but died soon afterwards. At

another time, when at sea, the captain and officers, when at dinner, heard the

alarm of a slave's being overboard, and found it true, for they perceived him

making every exertion to drown himself. He put his head under water, but

lifted his hands up; and thus went down, as if exulting that he had got away.

Besides the above instance, a man slave who came on board apparently well,

became afterwards mad, and at length died insane.

Mr. Claxton, the fourth surgeon examined on these points, declares the

steerage and boy's room to have been insufficient to receive the sick; they

were therefore obliged to place together those that were and those that were

not diseased, and in consequence the disease and mortality spread more and

more. The captain treated them with more tenderness than he has heard was

usual, but the men were not humane. Some of the most diseased were obliged

to keep on deck with a sail spread for them to lie on. This, in a little time,

became nearly covered with blood and mucus, which involuntarily issues from

them, and therefore the sailors, who had the disagreeable task of cleaning the

sail, grew angry with the slaves, and used to beat them inhumanly with their

hands, or with a cat. The slaves in consequence grew fearful of committing

this involuntary action, and when they perceived they had done it would im-

mediately creep to the tubs, and there sit straining with such violence, as to

produce a prolapsus ani, which could not be cured.

Some of the slaves on board the same ship, says Mr. Claxton, had such

an aversion to leaving their native places, that they threw themselves over-

board, on an idea that they should get back to their own country. The cap-

tain, in order to obviate this idea, thought of an expedient, viz: to cut off the

heads of those who died, intimating to them, that if determined to go, they

must return without their heads. the slaves were accordingly brought up to

witness the operation. One of them seeing, when on deck, the carpenter

standing with his hatchet up ready to strike off the head of a dead slave, with

a violent exertion got loose, and flying to the place where the nettings had

been unloosed, in order to empty the tubs, he darted overboard. The ship

brought to, and a man was placed in the main chains to catch him, which he

perceiving, dived under water, and rising again at a distance from the ship,

made signs, which words cannot describe, expressive of his happiness in escap-

ing. He then went down, and was seen no more. This circumstance deterred

the captain from trying the expedient any more, and therefore he resolved for

the future (as he saw they were determined to throw themselves overboard) to

keep a strict watch; not withstanding which, some afterwards contrived to un-

loose the lashing, so that two actually threw themselves into the sea, and were

lost; another was caught when about three parts overboard.

All the above incidents, described as to have happened on the Middle Pas-

sage, are amply corroborated by the other witnesses. The slaves lie on the

bare boards, says surgeon Wilson. They are frequently bruised, and the prom-

inent parts of the body excoriated, adds the same gentleman, as also Trotter

and Newton. They have been seen by Morley wallowing in their blood and

excrement. Claxton, Ellison, and Hall describe them as refusing sustenance,

and compelled to eat by the whip. Morley has seen the pannekin dashed

against their teeth, and the rice held in their mouths, to make them swallow it,

till they were almost strangled, and they have even been thumb-screwed* with

this view in the ships of Towne and Millar. The man stolen at Galenas river,

says the former, also refused to eat, and persisted till he died. A woman, says

the latter, who was brought on board, refused sustenance, neither would she

speak. She was then ordered the thumb-screws, suspended in the mizzen rig-

ging, and every attempt was made with the cat to compel her to eat, but to no

purpose. She died in three or four days afterwards. Mr. Millar was told that

she had said, the night before she died, "She was going to her friends."

As a third specific instance, in another vessel, may be mentioned that related

by Mr. Isaac Parker. there was a child, says he, on board, nine months old,

which refused to eat. for which the captain took it up in his hand, and flogged

it with a cat, saying, at the same time, "Damn you, I'll make you eat; or I'll

kill you." The same child having swelled feet, the captain ordered them to

be put into water, through the ship's cook told him it was too hot. This brought

off the skin and nails. He then ordered sweet oil and cloths, which Isaac Par-

ker himself applied to the feet; and as the child at mess time again refused to

eat, the captain again took it up and flogged it and tied a log of mango-wood

eighteen or twenty inches long, and of twelve or thirteen pounds weight, round

its neck, as a punishment. He repeated the flogging for four days together at

mess time. The last time after flogging it, he let it drop out of his hand, with

the same expression as before, and accordingly in about three quarters of an

hour the child died. He then called its mother to heave it overboard, and beat

her for refusing. He however forced her to take it up, and go to the ship's

side, where, holding her head on one side, to avoid the sight, she dropped

he child overboard, after which she cried for many hours.

Besides instances of slaves refusing to eat, with the view of destroying them-

selves, and dying in consequence of it, those of their going mad are confirmed

by Towne, and of their jumping overboard, or attempting to do it, by Towne,

Millar, Ellison, and Hall.

Other incidents on the passage, mentioned by some of the witnesses in their

examination, may be divided into three kinds:

The first kind consists of insurrections on the part of the slaves. Some of

these frequently attempted to rise, but were prevented, (Wilson, Towne, Trot-

* To show the severity of this punishment, Mr. Dove says, that while two slaves were

under the torture of the thumb-screws, the sweat ran down their faces, and they trem-

bled as under a violent ague fit; and Mr. Ellison has known instances of their dying, a

mortification having taken place in their thumbs in consequence of these screws.

ter, Newton, Dalrymple, Ellison,) others rose, but were quelled, (Ellison, New-

ton, Falconbridge,) and others rose and succeeded, killing almost all the whites:

(Falconbridge and Towne.) Mr. Towne says that , inquiring of the slaves into

the cause of these insurrections, he has been asked what business he had to

carry them from their country. They had wives and children, whom they wanted

to be with. After an insurrection, Mr. Ellison says he has seen them flogged,

and the cook's tormentors and tongs heated to burn the flesh. Mr. Newton

also adds that it is usual for captains, after insurrections and plots happen, to

flog the slaves. Some captains, on board whose ships he has been, added the

thumb-screw, and one in particular told him repeatedly that he had put slaves

to death,after an insurrection, by various modes of torture.

The second sort of incident on the passage is mentioned by Mr. Falconbridge

in the instance of an English vessel blowing up off Galenas, and most of the

men-slaves, entangled in their irons, perishing.

The third sort is described by Mr. Hercules Ross as follows. One instance,

says he, marked with peculiar circumstances of horror, occurs:--About twenty

years ago a ship from Africa, with about four hundred slaves on board, struck

upon some shoals, called the Morant Keys, distant eleven leagues, S.S.E. off

the east end of Jamaica. The officers and seamen of the ship landed in their

boats, carrying with them arms and provisions. The slaves were left on board

in their irons and shackles. This happened in the night time. The Morant

Keys consist of three small sandy islands, and he understood that the ship had

struck upon the shoals, at about half a league to windward of them. When

morning came, it was discovered that the negroes had got out of their irons,

and were busy making rafts, upon which they placed the women and children,

whilst the men, and others capable of swimming, attended upon the rafts, while

they drifted before the wind towards the island where the seamen had landed.

From an apprehension that the negroes would consume the water and provis-

ions which the seamen had landed, they came to the resolution of destroying

them by means of their fire-arms and other weapons. As the poor wretches

approached the shore, they actually destroyed between three and four hun-

dred of them. Out of the whole cargo, only thirty-three or thirty-four were

saved, and brought to Kingston, where Mr. Ross saw them sold at public ven-

due. The ship, to the best of his recollection, was consigned to a Mr. Hugh

Wallace, of the parish of St. Elizabeth's. Mr. Ross says, in extenuation of

this massacre, that the crew were probably drunk, or they would not have acted

so, but he does not know it to have been the case.

When the ships arrive at their destined ports, the slaves are exposed to sale.

They are sold either by scramble, by public auction, or by lots. The sale by

scramble is thus described by Mr. Falconbridge: "In the Emilia, at Jamaica,

the ship was darkened with sails, and covered around. The men-slaves were

placed on the main deck, and the women on the quarter deck. the purchasers

on shore were informed that a gun would be fired when they were ready to open

the sale. A great number of people came on board with tallies or cards in

their hands, with their own names on them, and rushed through the barricado

door with the ferocity or brutes. Some had three or four handkerchiefs tied

together, to encircle as many as they thought fit for their purpose. In the yard

at Grenada, he adds, (where another of his ships, the Alexander, sold by scram-

ble,) the women were so terrified, that several of them got out of the yard, and

ran about St. George's town as if they were mad. In his second voyage, while

lying at Kingston, he saw a sale by scramble on board the Tryal, Captain Mac-

donald. Forty or fifty of the slaves leaped into the sea, all of whom, how-

ever, were taken up again." This was a vary general mode of sale Mr. Bail-

lid says it was the common mode in America where he has been. Mr. Fitz-

maurice has been at twenty sales by scramble in Jamaica. Mr. Clappeson

never saw any other mode of sale during his residence there, and it is men-

tioned as having been practiced under the inspection of Morley and of Trotter.

The slaves sold by public auction are generally the refuse, of sickly slaves.

These were in such a state of health that they sold, says Baillie, greatly under

price. Falconbridge has known them sold for five dollars each, Town for a

guinea, and Mr Hercules Ross as low as a single dollar.

The state of such is described to be very deplorable by General Tottenham

and Mr. Hercules Toss. The former says that he once observed at Barbadoes

a number of slaves that had been landed from a ship. They were brought

into the yard adjoining the place of sale. Those that were not very ill were

put into little huts, and those that were worse were left in the yard to die,

for nobody gave them any thing to eat or drink; and some of them lived

three days in that situation. The latter has frequently seen the very refuse

(as they are termed) of the slaves of Guinea ships landed and carried to the

vendue-masters in a very wretched state; sometimes in the agonies of death;

and he has known instances of their expiring in the piazza of the auctioneer.

Mr. Newton says, that in none of the sales he saw was there any care ever

taken to prevent such slaves as were relations from being separated. They

were separated as sheep and lambs by the butcher. This separation of rela-

tions and friends is confirmed by Davison, Trotter, Clapperson, and Towne.

Fitzmaurice also mentions the same, with an exception only to infants; but

Mr. Falconbridge says that one of his captains (Frazer) recommended it to

the planters never to separate relations and friends. He says he once heard

of a person refusing to purchase a man's wife, and was next day informed the

man hanged himself.

With respect to the mortality of slaves in the passage, Mr. Falconbridge

says, that in three voyages he purchased, 1,100 and lost 191; Trotter, in one

voyage, about 600, and lost about 70; Millar, in one voyage, 490, and lost

180; Ellison, in three voyages, where he recollects the mortality, bought 895,

and lost 356. In one of these voyages, says the latter, the slaves had the

small-pox. In this case he has seen the platform one continued scab; eight

or ten of them were hauled up dead in a morning, and the flesh and skin peeled

off their wrists when taken hold of.

Mr. Morley says that in four voyages he purchased about 1,325, and lost

about 313. Mr. Towne, in two voyages, 630, and lost 115. Mr. Claxton, in

one voyage, 250, and lost 132. In this voyage, he says, they were so straighten-

end for provisions, that if they had been ten more days at sea, they must either

have eaten the slaves that died, of have made the living slaves walk the plank,

a term used among Guinea captains for making the slaves throw themselves

overboard. He says, also, that he fell in with the Hero, Captain Withers,

which had lost 360 slaves, or more than half her cargo, by the small-pox

The surgeon of the Hero told him that when the slaves were removed from

one place to another, they left marks of their skin and blood upon the deck, and

it was the most horrid sight he had ever seen.

Mr. Wilson states that in his ship and three others belonging to the same

concern, they purchased among them 2064 slaves, and lost 586. He adds, that

he fell in with the Hero, Captain Withers, at St. Thomas', which had lost 159

slaves by small-pox Captain Hall, in two voyages, purchased 550, and

lost 110. He adds, that he has known some ships in the slave-trade bury a

quarter, some a third, and others half of their cargo. It is very uncommon

to find ships without some loss* in their slaves.

Besides those which die on the passage, it must be noticed here that several

die soon after they are sold. Sixteen, says Mr. Falconbridge, were sold by

auction out of the Alexander, all of whom died before the ship left the West

Indies. Out of fourteen, says Mr. Claxton, sold from his ship in an infectious

state, only four lived; and through in the four voyages mentioned by Mr. Wil-

son, no less than 586 perished on the passage out of 2,064, yet 220 addition-

ally died of the small-pox in a very little time after their delivery in the river

Plate, making the total loss for those ships not less than 836, out of 2,064.

The causes of the disorders which carry off the slaves in such numbers, are

ascribed by Mr. Falconbridge to a diseased mind, sudden transitions from heat

to cold, a putrid atmosphere, wallowing in their own excrements, and being

shackled together. A diseased mind, he says, is undoubtedly one of the causes;

for many of the slaves on board refused medicines, giving as a reason, that

they wanted to die, and could never be cured. Some few, on the other hand,

who did not appear to think so much of their situation, recovered. That

shackling together is also another cause, was evident from the circumstance of

the men dying in twice the proportion the women did; and so long as the

trade continues, he adds, they must be shackled together, for no man will at-

tempt to carry them out of irons.

Surgeon Wilson, examined on the same topic, speaks nearly in the same

manner. He says that of the death of two-thirds of those who died in his

ship, the primary cause was melancholy. This was evident, not only from the

symptoms of the disorder, and the circumstance that no one who had it was

ever cured, whereas those who had it not, and yet were ill, recovered; but

from the language of the slaves themselves, who declared that they wished to

die, as also from Captain Smith's own declaration, who said their deaths were

*Total purchased, 7,904, lost 2,053, exclusive of the Hero, being above one-fourth

of the number purchased. The reader will observe that Mr. Claxton fell in with the

Hero on one voyage, and Mr. Wilson on another.

to be ascribed to their thinking so much of their situation. Though several

died of the flux, he attributes their death, primarily, to the cause before assign-

ed; for, says he, their original disorder was a fixed melancholy, and the symp-

toms, lowness of spirits and despondency. Hence the refused food. This

only increased the symptoms.

Mr. Towne, the only other person who speaks of the causes of the disorders

of the slaves, says "they often fall sick, sometimes owing to their crowded

state, but mostly to grief for being carried away from their country and friends."

This he knows from inquiring frequently (which he was enabled to do by

understanding their language) into the circumstances of their grievous com-

plaints.

We make some further extracts from the evidence, to exhibit the disastrous

and fatal effects of the trade upon the seamen engaged in it. Such was the

despotic character of the discipline on board of the slave-ships, and such the

insensibility to suffering acquired by the officers, that the condition of the sea-

men was not much better than that of the slaves. To exhibit the mortality

among the seamen on board these infected ships, a report was made to the

house of Commons, giving an abstract of the muster-rolls of such Liverpool and

Bristol ships as were returned to the custom houses from September, 1784, to

January, 1790. During this period, it appears that in 350 vessels, 12,263 sea-

men were employed; of these, only 5,760 returned home of the original crews;

of the remaining 6,503, there had died, before the vessels arrived in the West

Indies, 2,643. The fate of the 3,860, not accounted for in the muster-rolls,

we gather from the witnesses.

The crews of the African slavers, says Captain Hall, when they arrive in

the West Indies, are generally (he does not know a single instance to the con-

trary) in a sickly, debilitated state, and the seamen, who are discharged or

desert from those ships in the West Indies, are the most miserable objects he

ever met with in any country in his life. He has frequently seen them with

their toes rotted off, their legs swelled to the size of their thighs, and in an

ulcerated state all over. He has seen them on the different wharves in the

islands of Antigua, Barbadoes, and Jamaica, particularly at the two last

islands. He has also seen them laying under the cranes and balconies of the

houses near the water-side in Barbadoes and Jamaica expiring, and some quite

dead.

To confirm the assertion of Captain Hall, of the merchant service, that the

crews of Guinea-men generally arrive at their destined ports of sale in a sickly,

debilitates state, we may refer to Captain Hall, of the navy, who asserts that

in taking men (while in the West Indies) out of the merchant ships for the king's

service, he has, in taking a part of the crew of a Guinea ship, whose number

then consisted of seventy, been able to select but thirty, who could have been

thought capable of serving on board any ships of war, and when those thirty

were surveyed by order of the admiral, he was reprimanded for bringing such

men into the service, who were more likely to breed distemper than to be of

any use, and this at a time when seamen were so much wanted, that almost

any thing would have been taken. He adds also that this was not a singular

instance, but that it was generally the case; for he had many opportunities

between the years 1769 and 1773 of seeing the great distresses of crews of

Guinea ships, when they arrived in the West Indies.

We may refer also to Captain Smith, of the navy, who asserts that though

he may have boarded near twenty of these vessels in the West Indies, for the

purpose of impressing men, he was never able to get more than two men.

The principal reason was the fear of infection, having seen many of them in a

very disordered and ulcerated state.

The assertion also of Captain Hall, of the merchant service, relative to

their situation after their arrival at their destined ports of sale, is confirmed

by the rest of the witnesses in the minutest manner; for the seamen belonging

to the slave-vessels are described as lying about the wharves and cranes, or

wandering about the streets or islands full of sores and ulcers. It is asserted

by the witnesses, that they never saw any other than Guinea seamen in that

state in the West Indies. The epithets also of sickly, emaciated, abject, de-

plorable objects, are applied to them. They are mentioned again as desti-

tute, and starving, and without the means of support, no merchantmen taking

them in because they are unable to work, and men-of-war refusing them them for

fear of infection. Many of them are also described as lying about in a

dying state; and others have been actually found dead, and negroes have

been seen carrying the bodies of others to be interred.

It may be remarked here, that this diseased and forlorn state of the seamen

was so inseparable from the slave-trade, that the different witnesses had not only

seen it at Jamaica, Antigua, and Barbadoes, the places mentioned by Captain

Hall, but wherever they have seen Guinea-men arrive, namely, at St. Vincents,

Grenada, Dominique, and North America also.

The reasons why such immense numbers were left behind in the West Indies,

as were found in this deplorable state, are the following: The seamen leave

their ships from ill usage, says Ellison. It is usual for captains, say Clappe-

son and Young, to treat them ill, that they may desert and forfeit their wages.

Three others state they were left behind purposely by their captains; and Mr.

H. Rose adds in these emphatical words, "that it was no uncommon thing for

the captains to send on shore, a few hours before they sail, their lame, emaci-

ated, and sick seamen, leaving them to perish.

That the seamen employed in the slave-trade were worse fed, both in point

of quantity and quality or provisions, than the seamen in other trades, was

allowed by most of the witnesses, and that they had little or no shelter night

or day from the inclemency of the weather, during the whole of the Middle

Passage, was acknowledged by them all. With respect to their personal ill

usage, the following extracts may suffice:

Mr. Morley asserts that the seamen in all the Guinea-men he sailed in,

except one, were generally treated with great rigor, and many with cruelty.

He recollects many instances: Mathews, the chief mate of the Venus, Captain

Forbes, would knock a man down for any frivolous thing with a cat, a piece of

wood, or a cook's axe, with which he once cut a man down the shoulder, by

throwing it at him in a passion. Captain Dixon, likewise, in the Amelia, tied

up the men, and gave them four or five dozen lashes at a time, and then

rubbed them with pickle. Mr. Morley also himself, when he was Dixon's

cabin-boy, for accidentally breaking a glass, was tied to the tiller by the hands,

flogged with a cat, and kept hanging for some time. Mr. Morley has seen the

seamen lie and die upon the deck. They are generally, he says, treated ill

when sick. He has known men ask to have their wounds or ulcers dressed;

and has heard the doctor, with oaths, refuse to dress them.

Mr. Ellison also, in describing the treatment in the Briton, says there was a

boy on board, whom Wilson, the chief mate, was always beating. One morn-

ing, in the passage out, he had not got the tea-kettle boiled in time for his

breakfast, upon which, when it was brought, Wilson told him he would severely

flog him after breakfast. The boy, for fear of this, went into the lee for

chains. When Wilson came from the cabin, and called for Paddy, (the name

he went by, being an Irish boy,) he would not come, but remained in the fore

chains; on which Wilson going forward, and attempting to haul him in, the

boy jumped overboard, and was drowned.

Another time on the Middle Passage, the same Wilson ordered one James

Allison (a man he had been continually beating for trifles) to go into the

women's room to scrape it. Allison sad he was not able for he was very

unwell; upon which Wilson obliged him to go down. Observing, however,

that the man did not work, he asked him the reason, and was answered as

before, "that he was not able." Upon this, Wilson threw a handspike at him,

which struck him on the breast, and he dropped down to appearance dead.

Allison recovered afterwards a little, but died the next day.

Mr. Ellison relates other instances of ill-usage on board his own ship, and

with respect to instances in others, he says, that in all slave ships they are most

commonly beaten and knocked about for nothing. He recollects that on board

the Phœnix, a Bristol ship, while lying on the coast, the boatswain and five of

the crew made their escape in the yawl, but were taken up by the natives.

When Captain Bishop heard it, he ordered them to be kept on shore at Forje,

a small town at the mouth of the Calabar River, chained by the necks, legs, and

hands, and to have each a plantain a day only. The boatswain, whose name

was Tom Jones, and an old shipmate of his, and a very good seamen, died

raving mad in his chains there. The other five died in their chains also.

Mr. Towne, in speaking of the treatment on board the Peggy, Captain

Davison, says that their chests were brought upon deck, and staved and burnt,

and themselves turned out from lying below; and if any murmurs were heard

among them, they were inhumanly beaten with any thing that came in the way,

or flogged, both legs put in irons, and chained abaft to the pumps, and there

made to work points and gaskets, during the captain's pleasure; and very

often beat just as the captain thought proper. He himself has often seen the

captain as he has walked by, kick them repeatedly, and if they have said any

thing that he might deem offensive, he has immediately called for a stick to

beat them with; they at the same time, having both legs in irons, an iron col-

lar about their necks, and a chain; and when on the coast of Guinea, if not

released before their arrival there from their confinement, they were put into

the boats, and made to row backwards and forwards, either with the captain

from ship to ship, or on any other duty, still both legs in irons, an iron collar

about their necks, with a chain locked to the boat, and taken out when no other

duty was required of them at night, and locked fast upon the open deck, ex-

posed to the heavy rains and dews, without any thing to lie upon, or any thing

to cover them. This was a practice on board the Peggy.

He says, also, that similar treatment prevailed on board the Sally, another

ship on which he sailed. One of the seamen had both legs in irons, and a col-

lar about his neck, and was chained to the boat for three months, and very often

inhumanly beaten for complaining of his situation, both by the captain and

other officers. At last he became so weak that he could not sit upon the

thwart or seat of the boat to row, or do anything else. They then put him

out of the boat, and made him pick oakum on board the ship, with only three

pounds of bread a week, and half a pound of salt beef per day. He remain-

ed in that situation, with both his legs in irons, but the latter part of the time

without a collar. One evening he came aft, during the middle passage, to beg

something to eat, or he should die. The captain on this inhumanly beat him,

and used a great number of reproaches, and ordered him to go forward, and

die and be damned. The man died in the night. The ill treatment on board

the Sally was general.

As another particular instance, a landsman, one Edw. Hilton, was in the boat

watering, and complained of his being long in the boat without meat or drink.

The boatswain, being the officer, beat him with the boat's tiller, having nothing

else, and cut his dead in several places, so that when he come on board he was

all over blood. Mr. Towne asked him the reason of it. Hiton began to tell

him, but before he could properly tell the story, the mate came forward, (by

order of the captain) the surgeon and the boatswain, and all of them together

fell to beating him with their canes. The surgeon struck him on the side of

his eye, so that it afterwards mortified, and was lost. He immediately had both

his legs put in irons, and locked with a chain to the boat, until such

time as he became so weak that he was not able to remain any longer there.

He was then put on board the ship, and laid forwards, still in irons, very ill.

His allowance was immediately stopped, as it was the surgeon's opinion it was

the only method of curing any one of them who complained of illness. He

remained in that situation, after being taken out of the boat, for some weeks

after. During this time, Mr. Towne was obliged to go to Junk River, and

on his return he inquired for Hilton, and was told that he was lying before the

foremast, almost dead. He went and spoke to him. but Hilton seemed insen-

sible. The same day Mr. Towne received his orders to go a second time in

the shallop to Junk River. After he had gotten under weigh, the commander

of the shallop was ordered to bring to, and take Hilton in, and leave him on

shore any where. He lived that evening and night out, and died early the

next morning, and was thrown overboard off Cape Mesurado.

Mr. Falconbridge, being called upon also to speak to the ill usage of sea-

men, said that on board the Alexander, Captain M'Taggart, he has seen them

tied up and flogged with the cat frequently. He remembers also an instance

of an old man, who was boatswain of the Alexander, having one night some

words with the mate, when the boatswain was severely beaten, and had one or

two of his teeth knocked out. The boatswain said he would jump overboard;

upon which he was tied to the rail of the quarter-deck, and a pump-bolt put

into his mouth by way of gagging him. He was then untied, put under the

half-deck, and a sentinel put over him all night--in the morning he was re-

leased. Mr. Falconbridge always considered him as a quiet, inoffensive man.

In the same voyage a black boy was beaten every day, and one day after he

was so beaten, he jumped through on of the gun-ports of the cabin into the

river. A canoe was lying alongside, which dropped astern and picked him up.

Mr. Falconbridge gave him one of his own shirts to put on, and asked him if

he did not expect to be devoured by the sharks. The boy said he did, and

that it would be much better for him to be killed at once, than to be daily

treated with such cruelty.

Mr. Falconbridge remembers also, on board the same ship, that the black

cook one day broke a plate. For this he had a fish-gig darted at him, which

would certainly have destroyed him if he had not stooped or dropped down.

At another time also, the carpenter's mate had let his pitch-pot catch fire.

He and the cook were accordingly both tied up, stripped and flogged, but the

cook with the greatest severity. After that the cook had salt water and cay-

enne pepper rubbed on his back. A man also came on board at Bonny,

belonging to a little ship, (Mr. Falconbridge believes the captain's name was

Dodson, of Liverpool,) which had been overset at New Calabar. This man,

when he came on board, was in a convalescent state. He was severely beaten

one night, but for what cause Mr. Falconbridge knows not, upon which he

came to Mr. Falconbridge for something to rub his back with. Mr. Falcon-

bridge was told by the captain not to give him any thing, and the man was

desired to go forward. He went accordingly, and lay under the forecastle.

Mr. Falconbridge visited him very often, at which times he complained of his

bruises. He died in about three weeks from the time he was beaten. The

last words he ever spoke were, after shedding tears, "I cannot punish him,"

meaning the captain, "but God will." These are the most remarkable in-

stances which Mr. Falconbridge recollects. He says, however, that the ill

treatment was so general, that only three in this ship escaped being beaten out

of fifty persons.

To these instances, which fell under the eyes of the witnesses now cited, we

may add the observations of a gentleman who, though never in the slave-trade

had yet great opportunities of obtaining information upon this subject. Sir

George Young remarks, that those seamen whom he saw in the slave-trade,

while on the coast in a man-of-war, complained of their ill treatment, bad feed-

ing, and cruel usage. They all wanted to enter on board his ship. It was like-

wise the custom for the seamen of every ship he saw at a distance, to come on

board him with their boats; most of them quite naked, and threatening to turn

pirates if he did not take them. This they told him openly. He is persuaded,

if he had given them encouragement, and had a ship-of-the-line to have

manned, he could have done it in a very short time, for they would all have left

their ships. He has also received several seamen on board his ship from the

woods, where they had no subsistence, but to which they had fled for refuge

from their respective vessels.

That the above are not the only instances of barbarity contained in the evi-

dence, and that this barbarous usage was peculiar to, or springing out of the

very nature of the trade in slaves, may be insisted on the following accounts:

Captain Thompson concludes from the many complaints he received from

seamen, while on the coast, that they are far from being well treated on board

the slave-ships. One Bowden swam from the Fisher, of Liverpool, Captain

Kendal, to the Nautilus, amidst a number of sharks, to claim his protection.

Kendal wrote for the man, who refused to return, saying his life would be en-

dangered. He therefore kept him in the Nautilus till she was paid off, and

found him a diligent, willing, active seaman. Several of the crew, he thinks,

of the Brothers, of Liverpool, Captain Clark, swam towards the Nautilus,

when passing by. Two only reached her. The rest, he believes, regained

their own ship. The majority of the crew had the day before come on board

the Nautilus, in a boat, to complain of ill usage, be he had returned them

with an officer to inquire into and redress their complaints. He received many

letters from seamen in slave-ships, complaining of ill usage, and desiring him

to protect them, or take them on board. He is inclined to think that ships

trading in the produce of Africa, are not so ill used as those in the slave-ships.

Several of his own officers gave him the best accounts of the treatment in the

Iris, a vessel trading for wood, gums, and ivory, near which the Nautilus lay

for some weeks.

Lieutenant Simpson says that on his first voyage, when lying at Fort Appo-

lonia, the Fly Guineaman was in the roads. On the return of the Adventure's

boat from the fort, they were hailed by some seamen belonging to the Fly, re-

questing that they might be taken from on board the Guineaman, and put on

board the man-of-war, for that their treatment was such as to make their lives

miserable. The boat, by the direction of Captain Parry, was sent to the Fly,

and one or two men were brought on board him. In his second voyage, he re-

collects that on first seeing the Albion Guineaman, she carried a press of sail,

seemingly to avoid them, but finding it impracticable, she spoke them; the day

after which the captain of the Albion Guineaman, she carried a press of sail,

seemingly to avoid them, but finding it impracticable, she spoke them; the day

after which the captain of the Albion brought a seamen on board the Adven-

ture, whom he wished to be left there, complaining that he was a very riotous

and disorderly man. The man, on the contrary, proved very peaceable and

well-behaved, nor was there one single instance of his conduct from which he

could suppose he merited the character given him. He seemed to rejoice at

quitting the Albion, and informed Mr. Simpson that he was cruelly beaten both

by the captain and surgeon; that he was half starved; and that the surgeon

neglected the sick seamen, alleging that he was only paid for attending the

slaves. he also informed Mr. Simpson that their allowance of provisions was

increased, and their treatment somewhat better when a man-of-war was on the

coast. He recollects another instance of a seaman, with a leg shockingly ul-

cerated, requesting a passage in the Adventure to England; alleging that he

was left behind from a Guineaman. He alleged various instances of ill treat-

ment he had received, and confirmed the account of the sailor of the Albion,

that their allowonce of provisions was increased, and treatment better, when a

man-of-war was on the coast. During Mr. Simpson's stay at Cape Coast Cas-

tle, the Adventure's boat was sent to Annamaboe to the Spy Guineaman; on

her return, three men were concealed under her sails, who had left the slave-

ship; they complained that their treatment was so bad that their lives were

miserable on board--beaten and half starved. There were various other in-

stances which escaped his memory. Mr. Simpson says, however, that he has

never heard any complaints from West Indiamen, or other merchant ships; on

the contrary, they wished to avoid a man-of-war; whereas, if the captain of the

Adventure had listened to all the complaints made to him from sailors of slave-

ships, and removed them, he must have greatly distressed the African trade.

Captain Hall, of the navy, speaking on the same subject, asserts that as to

peculiar modes of punishment adopted in Guineamen, he once saw a man

chained by the neck in the main top of a slave-ship, when passing under the

stern of His majesty's ship Crescent, in Kingston-Bay, St. Vincent's; and was

told by part of the crew, taken out of the ship, at their own request, that the

man had been there one hundred and twenty days. He says he has great rea-

son to believe that in no trade are seamen so badly treated as in the slave-

trade, from their always flying to men-of-war for redress, and whenever they

came within reach; wheras men from West Indian or other trades seldom ap-

ply to a ship-of-war.

The last witness it will be necessary to cite is the Rev. Mr. Newton. This

gentleman agrees in the ill usage of the seamen alluded to, and believes that

the slave-trade itself is a great cause of it, for he thinks that the real or sup-

posed necessity of treating the negroes with rigor gradually brings a numness

upon the heart, and renders most of those who are engaged in it too indiffer-

ent to the sufferings of their fellow-creatures. If it should be asked how it

happened that seamen entered for slave-vessels, when such general ill usage

there could hardly fail of being known, the reply must be taken from the evi-

dence, "that whereas some of them enter voluntarily, the greater part of them

are trepanned, for that is the business of certain landlords to make them in-

toxicated, and get them into debt, after which their only alternative is a Guin-

eaman or a gaol."